Lagerstatten present an interesting, if morbid, paradox. The very processes which leads to exquisite fossil preservation for appreciation and study, while quite fortuitous from our point of view, are also horrible, no good, very bad ones for the object of our inquiry. Think extreme landslide or flood or eruption. Things that we ourselves would not want to be caught in the middle of. Still, these catastrophic events can sometimes provide an unparalleled view of the past. One of the finest examples of this in the world happens to be on a small hillside 3 hours outside Omaha, Nebraska. A few days ago I was lucky enough to finally visit the Ashfall Fossil Beds in Antelope County, NE.

Mantle plumes and hotspots are a subject most people with an interest in the Hawaiian archipelago are familiar with. The reliable and periodic eruptions of the Hawaiian hotspot combined with the steady movement of the Pacific plate resulted in a string of islands being carried away in a conveyor belt like manner. Hawai`i isn’t the only place on the planet where this happens. Another hotspot is under the intermountain west of North America. Here geologic features in the Snake River basin point to a series of gigantic eruptions dating to at least the mid Miocene. The hotspot that created these features is currently situated under NW Wyoming, where it is causing all the interesting geysers, hot springs, and geothermal activity of Yellowstone National Park.

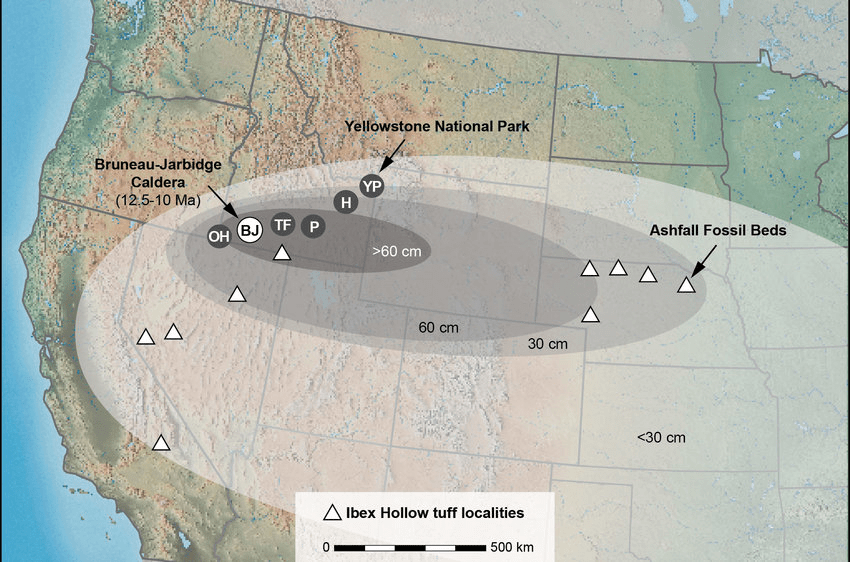

Each hotspot has its own unique characteristics. Conditions differ as well. The Hawaiian hotspot erupts through oceanic crust. The Yellowstone hotspot has to punch through accreted continental rock. Whatever the reason, the eruptions of said hotspots vary quite greatly. While most eruptions from the Hawaiian hotspot are fairly gentle, the same cannot be said about Yellowstone. For most people living around an active Hawaiian eruption, the most widespread effects are irritated sinuses from elevated gas emissions i.e. allergies. The Yellowstone hotspot erupts less frequently but with power orders of magnitude greater than in Hawai`i, blowing apart mountains and covering extensive parts of North America in thick ash.

The particular eruption that we are interested in for this post happened one day in Idaho 11.8 million years ago. Far away at in eastern Nebraska, ash eventually began to fall from this eruption. Indeed, most of Nebraska would have been covered in ash about a foot thick. Unlike allergies, this ash would have caused major deleterious effects on the local wildlife. Many animals sought refuge at a nearby waterhole where over the course of a few weeks they would eventually succumb to the effects from the eruption.

Nearly 12 million years later, we see that pond as it was on that day. (Ok, technically more like a month’s time) Not figuratively, like using your mind’s eye or needing a mural to reconstruct what we uncovered. Literally see the waterhole. Paleontology interns from the University of Nebraska scrape away the ash until they reach the algal mat indicating they’ve hit the waterhole layer. It basically looks like the ash and then sandstone covered over it all like a cap, leaving everything in place for us to unveil later. We have a spectacularly clear picture of an event almost 12 million years ago, with all the animals in such life-like poses that we can feel their pain.

What were those animals? If we close our eyes and think of typical large animals of the U.S, we think of deer, bison, bears, elk, wolves, perhaps moose. None of those animals were present at the ashfall site. Indeed, the entire deer family (cervidae) would not enter the continent for millions of years. However, ecosystems and faunal communities were already beginning to approach modern ones. Just not quite modern yet. Let’s take a look at some of these autochthonous denizens of Nebraska that would look strange to modern eyes.

Horses have a long and storied history in North America. From their beginnings as small dog-sized, 5-toed forest dwelling creatures to the large single-toed grazers of grasslands, horses left their mark on the North American landscape and, luckily, also in the fossil record. This is a case where it looks almost modern but not quite. While the animals look largely like the horses we’re familiar with, upon closer inspection one can see that many of the individuals had 3 fully functional toes. In this time period, many equid species were tridactyl. They were also much more diverse and a larger component of faunal communities in the Miocene as well, with a number of species living sympatrically. In a modern African savannah, there is typically only 1 species of equid: a zebra. At Ashfall alone, Pseudohipparion gratum, Neohipparion affine, Cormohipparion occidentale, Protohippus simus, Pliohippus pernix, and possibly even the odd Hypohippus were found interacting in the same environment.

The star of the show at the fossil bed is a taxa that most people don’t associate with America: American Rhinos. The clade aceratheriini was a group of rhinoceros that had a long history in the northern continents. In fact, rhinos as a whole flourished in the northern hemisphere during the Eocene in widespread tropical conditions. At the time of the ashfall event, 2 taxa of aceratheriini rhinoceratids were common in North America, Aphelops and Teleoceros. This species, T. major, is the most common fossil species found at the ashfall site. Roughly 100 individuals have been uncovered so far. There are so many that researchers can make some inferences on their behavior and ecology (possibly social in a harem structure with a distinct calving period).

This is the first time on Studia Mirabilium I get to mention them, but another component of the Ashfall fauna are the native dogs. I love borophaginine canids. Like horses, dogs seemed to have evolved in North America and were endemic solely to the continent for a significant portion of their evolutionary history. Borophaginines are a separate, earlier radiation of dogs from the familiar wolves, jackals, and foxes of today. In some parts of popular culture, the family is known as the bone-crushing dogs. While it’s true that the subfamily had large apex predators with hypertrophied molars for bone crushing (Epicyon, Borophagus), it’s only part of the story for me.

The subfamily was extraordinarily successful in the Miocene. The diversity of ecological niches they were able to occupy also impress me. Aside from hypercarnivorous and mesocarnivorous species, some borophaginines even evolved into more hypocarnivorous and almost herbivorous forms with Carpocyon, Cynarctus, Paracynarctus. I couldn’t get a good photo of it, but between 2 adult Teleoceras is a beautifully preserved Cynarctus specimen. As far as I know, it is the only mostly complete, articulated skeleton of a carnivore at the site.

When National Geographic helped fund the first digs in the late 70’s, they did the sort of standard practice at the time of digging everything out, putting it in plaster jackets and assembling it all back at a museum. It led to amazing complete mounted skeletons in protected indoor spaces but even then that process can ignore some context and data. The waterhole is basically intact with everything in place as it was that one month 12 million years ago. I’m not sure when the decision was made, but all excavations hence will be left in situ. Ashfall in a number of ways is similar to Pompeii. Instead of walking through a beautifully preserved Roman Town, we are strolling by a waterhole with the animals there as it was that fateful event. A sheltered barn was built in 2009 so that researchers and the adoring public can see everything in situ.

I mentioned in the one of my early posts on this blog how we culturally have a narrow band of numbers that have an intuitive feel and meaning with useful day to day applications. At some point differences between large numbers becomes this vague concept of “a lot”. The same can be said about paleontology. It’s hard for us to appreciate the span of time; it’s just “ancient”. The vast difference in time merges into this nebulous concept of “the past”. One analogy I find that gains some traction with people is to look at seconds. 1 million, 1 billion, 1 trillion. For a lot of folks, those are all similarly large numbers with just a letter difference. It’s just “a lot”. But a million seconds ago is when you start worrying about the leftovers in your fridge (12 days). A billion seconds ago is nostalgia for Depeche Mode and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (33 years). And a trillion seconds ago Woolly Mammoths and Sabertooths roamed the land (33,000 years ago).

Pompeii was about 2,000 years ago. Fossils from La Brea are about 40,000 years ago. The fantastic preservation at Ashfall makes it seem like these animals died yesterday. By looks alone, the ashfall fossils wouldn’t look out of place at either site. The quality of the fossils can mask how old they are. This coupled with our lack of feel for how far back into time we’re looking at can hide how special Ashfall is. I cannot stress enough how fortunate it is to have complete, articulated, 3D skeletons of creatures from 12 million years ago.

So is it worth the drive? There is not much else to do in this part of Nebraska for the average tourist. You’re making the pilgrimage just for Ashfall. For me though, the answer is a resounding yes. I could have spent all day at the site. The staff and docents are all super friendly and happy to field any questions about the location. You can watch interns meticulously working away at the ash to unveil fossils. It’s still an ongoing, working dig site. The main fossil bed is in an enclosed, climate controlled facility; it makes for a pleasurable viewing experience. Bring some snacks or lunch to take advantage of some of the picnic tables they have around. But being able to be transported back in time, to walk the edge of the waterhole as it looked after that fateful event, and to see such a clear snapshot of life in the Clarendonian made it an unforgettable experience for me. If you ever find yourself in Omaha and have any interest in North American land mammals, make a day of it and drive to this special place.

——P.S. I chuckled as I wrote this post. I write a lot about native Hawaiian biota and filter things through that lens. Yet when I look at the banner for this blog that I made 13 years ago, it has multiple rhinos on it. And what is today’s post, more rhinos! Studia Mirabilium: the study of marvelous Hawaiian plants and rhinos. Until next time.

For more details, visit Ashfall Fossil Beds

Pingback: Who let the dogs out? Wolves, Coyotes and the Post-Hemphilian Canis radiation | Studia Mirabilium