So this post may just be an excuse for me to post more photos from my trip to the Living Desert Zoo and Garden. While wolves and coyotes may look similar enough for the lay person like myself to confuse them, they have distinct evolutionary histories. It points to a question I have about what canine canids were doing after the collapse of the borphaginine canids and gives me another reason to use one of my favorite terms here at Studia Mirabilium: Autochthonous.

Let me be that narrator at the beginning of many live theater productions and set the stage. One of the more consequential extinction events for North American mammals happened at the end-Hemphilian roughly 4 million years ago. Prior to that, the large mammal guild would have felt way more exotic to modern eyes with things like rhinos and long-necked camels resembling giraffes on one end to completely bizarre taxa like clawed, dome-headed, moose-like horse relatives (Chalicotheres) on the other being some of the common animals of the North American landscape. After that event, the fauna started looking more modern and familiar with deer and bovids becoming more commonplace. My post on Ashfall highlights some of the common animals of this exotic world.

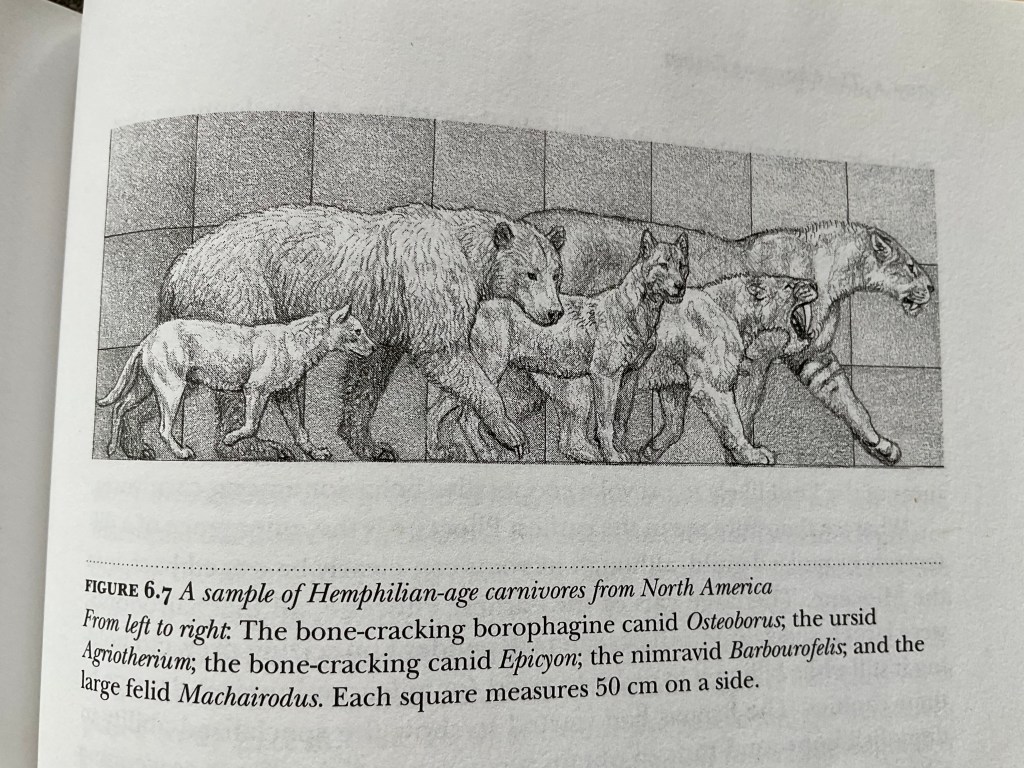

The large carnivore guild of the Hemphilian was just as strange. While there were apex predators from the felid and ursid lineages, a surprising number, at least to modern eyes, were canids. To put it another way, there were a whole bunch of dogs running around the prairies and woodlands of North America. There was the lion-sized Epicyon haydeni, it’s smaller cousin E. saeveus, there was a bone-cracking Borophagus with especially hypertrophied molars, and there was Aelurodon, a wolf-sized dog with teeth more specialized for flesh-eating that wolves. No modern ecosystem had that many large dogs living sympatrically. In much of the modern Holoartic, wolves are the only large canids around. In Africa, hunting dogs are the sole representative. The only place I can think of is certain parts of subtropical Asia, where wolves and dholes (Cuon alpinus) co-exist. This doesn’t even include the more hypocarnivorous forms; the number of different Borophaginine canids in an average North American environment was impressive.

As successful as these dogs were, none of them were the familiar wolves, wild dogs and foxes. Borophaginine canids were a separate branch of the dog family from the familiar canine canids of today. Living at the same time and in the shadow of these large canids was the probable precursor to many of todays dogs: Eucyon. And its tale involves new lands to conquer, new forms, and a reinvasion of its homeland.

Dog evolved in North America in the late Eocene some 37 million years ago. For much of the dog family’s evolutionary history, they were endemic to their home continent of North America. In Eurasia, what seemed to have taken their place were dog-like Hyaenas. We think of hyaenas has large scavenging forms today, but during the Miocene they were very successful and occupied many types of niches. But an extinction event just as consequential as the end-Hemphilian happened in Eurasia, with many species going extinct. The hyaenids were especially hard hit.

The next land mammal age (Blancan in North America) was a time of transition. Eucyon and its descendant Canis began diversifying. But at the same time the last of the great Hyaenid and Borophaginine canid lineages (Chasmaporthetes and Borophagus respectively) were still around. Both species seem to die out just as the Ice Ages began.

With the extinctions of both lineages on 2 continents and a landbridge connection to a third (Africa), canine canids were able to exploit niches in a huge range. While there was a record of older hespercyonine canids in Miocene China, it seemed that it was not until canine canids erupted on the scene that dogs became prevalent outside of North America. Eurasia seemed to be a hotbed of Canis evolution with C. etruscus, C. chihiliensis, C. mosbachensis possibly being ancestors to wolves (Canis lupus). Meanwhile, a working theory is that Canis lepophagus and C. edwardsii were precursors to the coyote (Canis latrans).

What fascinates me were the autochthonous populations of Canis still in North America. After the extinction of their competitors (dog-like hyaenas and the large borophaginine canids) and their expansion into the old world, what were those dogs doing? I’ve read that both lineages of coyotes and wolves may have immigrated back to their original home continent from Eurasia. I’ve also read that coyote lineage being descended from Eucron davisi and through Canis lepophagus is autochthonous to North America. This doesn’t even take into consideration the red wolf, eastern North American wolves, North American “jackals” and the mighty dire wolf. Part of the difficulty is that Canis spp disperse widely and interbreed readily. With the potential for so much admixture, the populations on both continents could be seen as one contiguous populations. No one actually thinks of dogs that way; it brings into the conversation ideas of ecology, niche partitioning, species concepts. It just makes it difficult to sort through the various lineages as they evolved in the post-Hemphilian world. But for as much research seems to point at a lot of Canis evolution happening in Eurasia, I always wondered about the dog populations in North America.

These are the videos I took of the 2 native Canis dogs of North America at the Living Desert Zoo and Garden. Now, I could’ve have done a simple snapshot post highlighting the narrower muzzle and more pointed ears of the coyote compared to the wolf. But I wanted to at least bring out the very interesting evolutionary history of the 2 species. They are part of a great radiation of dogs that took advantage of the extinctions of an earlier radiation of dogs and spread through much of the world. Seeing these 2 dogs species in that light really humbles me: there have been thriving dog populations in the North American landscape for a long, long time. Let’s keep it that way.

For some interesting reading please check out the wonderful book Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History by Tedford & Wang